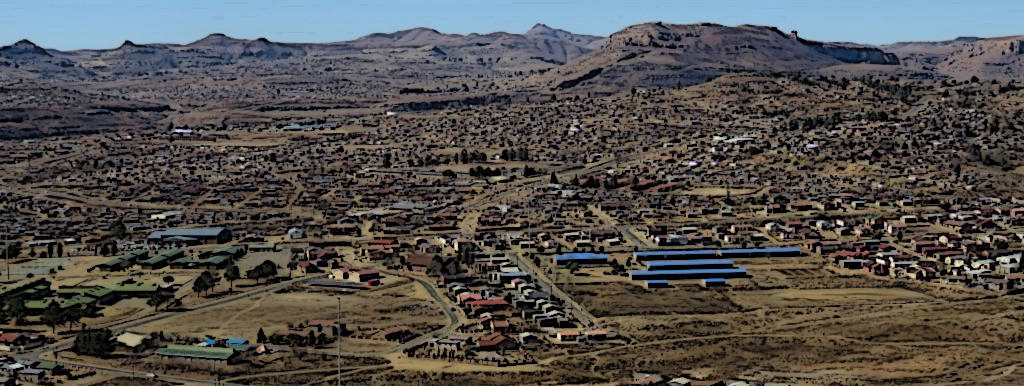

Chances are you have never heard of it. Well, it is a town in the Eastern Free State. And it’s not that small a place either – with at least 60 000 inhabitants. It spills through the foothills of the imposing Drakensberg mountains. There are two large malls there and the town centre is busy, rough and bustling. There is a university campus, a college and even a school for the blind. Also, for those who love their soccer, it is the birthplace of the Free State Stars. When I went there though, I discovered something else about Phuthaditjaba. I discovered blind people who were up and doing something about their lives.

The specific reason for my going to that place this time was to show a funder of ours how we had trained blind people there to use the white cane.

First, we met Vilakazi. He is called by his surname, it seems. Vilakazi works for the Phuthaditjaba municipality – at their disability desk. That is remarkable in itself when you think that well over 90% of blind people in South Africa are unemployed. Vilakazi, who is in his early thirties, gave the funder a brilliant demonstration of how well their money had been spent. He made his way with his white cane from the municipal offices to the spot where he catches a minibus taxi home each day. A short route but fraught with obstacles – street hawker stands; cars parked across the narrow pavement; raised manhole covers; puddles in pavement potholes: you name it. And he did it with confidence, dignity and a small smile on his face.

Kidibone, our trainer who had taught him how to do this, then passed him a certificate which he had specifically asked her for. The funder looked at it and read it out to him. Her voice was clear and quiet. It said: “… Vilakazi has successfully completed the Orientation and Mobility course run by the South African Mobility for the Blind Trust from July to September 2016 in Phuthaditjaba.”

Vilakazi then turned and said to the funder, “You know why I asked for this? I asked because I want it for my CV. I want this to show the employers that I will not be a burden to them. That’s why.”

He also said something else to the funder. It was this. “You must carry on doing what you are doing. You must not stop now.” Viva Vilakazi!

But that’s not the end of it. Not by any means. From there, we went on to the college. To the college? Why? Because there, there were seven of the people whom Kidibone had trained. And what were they doing? A computer course! A computer course for the blind in Phuthaditjaba? Well, well. And not only that. They also had students at that college with other disabilities, including some who were deaf.

Anyway, so here we all are now, sitting round a table at the college – me, the funder and seven blind people, all of them young.

The funder says, “Tell me about yourselves. Tell me how you lost your sight.”

And they do. And the stories are sad, of course.

He is a young man. He is a policeman on duty. There is a terrible car accident that he’s in and he comes out of it blind. But there was a mistake in the paperwork so now he can’t claim his workman’s compensation and he can’t pay his debts and he is very stressed because he has got two small children and …

And there is a young woman sitting here next to me. She was in her second year at university here. She got a terrible headache one day and now a lot of her sight is gone. She wants to go on with her university studies but there is a problem getting a bursary. The funder says, “We do bursaries. Talk to me after this.”

And then, there is Joyce. She was taken into hospital when she went blind. One night in the hospital she got up to go to the toilet, tripped and fell and broke her back and is now in a wheelchair as well because of that. But you know what? She’s here doing a computer course.

And now, we come to Simon, sitting across the table from me. He is a bit older than the others – about forty. I had met him once before here in Phuthaditjaba. There he was, coming back from the mall with a bag of food to be cooked for some other blind people at a self-help group up the hill. There they are trying to create work for those people. I noticed then with interest that he took down my contact details on a touch phone. I suspect that Simon is one of those behind much of what is going on here in Phuthaditjaba. Any way. He, unlike some of them around this table, knows why he went blind.

It was during the 2010 Soccer World Cup here in South Africa, he tells us. He and some of his friends were celebrating after a match up near Johannesburg where he worked at the time. In the morning he woke up with a blinding headache. He thought it was because they had been celebrating too much the night before. But it wasn’t. It was because he had contracted meningitis. He was in hospital for six months after that and he came out blind. Now he is here, back in Phuthaditjaba, doing what he does – not taking things lying down and bringing people with him.

And you know what? I who am blind myself, I came away from that place, Phuthaditjaba, knowing what I’ve always known. And that is that there is no such place as nowhere.